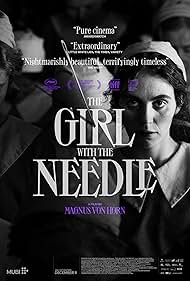

Copenhagen 1919: A young working girl finds herself unemployed and pregnant. She meets Dagmar, who runs an underground adoption agency. A strong connection develops, but her world is shattered when she stumbles upon the shocking truth behind her work. Official Danish submission for the 97th Academy Awards in 2025 for Best International Feature Film. As a journalist by training, I’m not usually one to shy away from a disturbing story, whether told through reporting or on the silver screen. However, there are times when I have to question whether certain films should be made in the first place. Just because it’s possible, in my opinion, doesn’t necessarily mean it should be. Such is the case with writer-director Magnus von Horn’s third feature, a dark, fact-based story that is inherently disturbing and, frankly, pushes the boundaries of good taste. The film, set in Copenhagen at the end of World War I, follows the life of Karoline (Vic Carmen Sonne), a factory seamstress whose husband, Peter (Besir Zeciri), is thought to have been killed in the conflict. In his absence, she befriends her boss, Jørgen (Joachim Fjelstrup), who gets her pregnant by him. He abandons her without warning when her wealthy and domineering mother (Benedikte Hansen) threatens to cut off her income if they marry. Karoline is left with the prospect of becoming an unemployed single mother. She takes drastic measures to terminate her pregnancy, but reconsiders her decision when she meets a seemingly sympathetic and supposedly legitimate but highly unscrupulous trader, Dagmar (Trine Dyrholm), who offers to help her out of her dilemma – for a price. Little does she know, however, that the price is much higher than she could have imagined, especially when she becomes involved with this new stranger and his completely unprincipled operation. What ensues is one of the most disturbing stories I have ever seen put to film, one that genuinely makes me wonder if it should have been told in the first place. Granted, this film is technically well-made, with gorgeous black-and-white cinematography and fine acting across the board. However, it is so cold and unsettling that even viewers with strong stomachs and unwavering filmmaking sensibilities may find this film difficult to watch. It might have worked better as a documentary than as a narrative reconstruction, but that is small comfort given the disturbing subject matter of this offering. It also makes me wonder how so many critics, awards shows and film festivals have come to lavish it with such praise, despite the undeniable technical prowess that went into making this film. These feats hardly seem to justify the existence of this film and represent a growing trend towards an inherently callous and irresponsible approach to filmmaking, an approach whose further development, in my opinion, should be nipped in the bud, however revolutionary, inventive and provocative it may be perceived to be. Some have tried to characterize “The Needle Girl” as a scary horror film, but in my view, I see it more as a horror film, a dubious distinction indeed. Indeed, don’t say you weren’t warned about this one.

48/36

48/36